|

Painted Poetry:

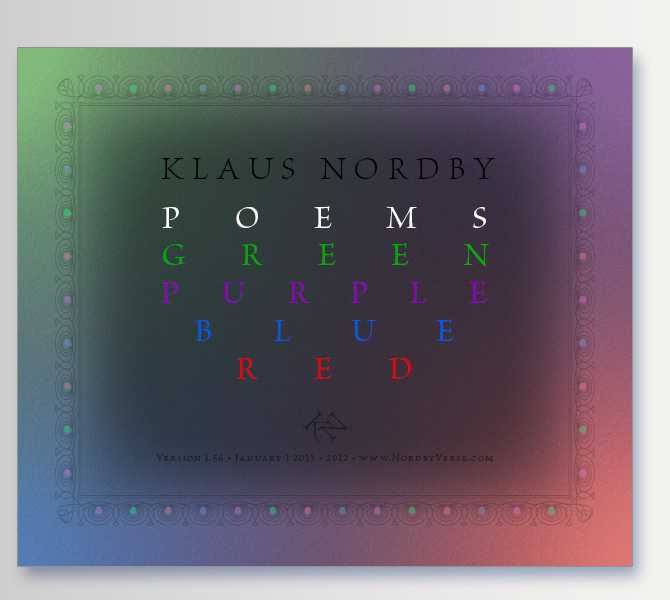

A review of Klaus Nordby’s

Poems Green Purple Blue Red

By John Kagebein © 2012

This is a four-part literary review of the poetic works of my friend, Klaus Nordby. A free PDF ebook of all 53 poems is available for download at www.NordbyVerse.com. Handsomely printed editions, in three price ranges, can be securely purchased via his webshop at www.Blurb.com/user/store/KlausNordby.

Part 1: Poems Green

According to Klaus Nordby, his Poems Green are “too silly”. They are certainly whimsical and charming.

The first two poems in this collection are tongue-in-cheek self-indulgences, concerning Nordby’s own poetic stylings.

In Lingo Bingo, he offers a humorous, linguistically illustrated insight into why he chooses to write in English, rather than his native Norwegian, through a series of coupled anapestic feet.

In Quo Vadis, O Novice?, he indulges in a bit of defiant self-effacement. That the anapestic trimeter is, occasionally, slightly forced and utilizes the device of contriving the odd extra syllable or two (such as wringing two syllables out of “stopped”), might seem to support the poem’s claim that “this Klaus is no Kipling or Keats”. But, whether intentionally or not, such contrivances actually serve to elevate my expectations of what is to come.

Next, comes a silly green, drunken ode, in iambic tetrameter. A Plastered Wound is deeper than it appears, but shallow enough to remain enjoyable after several pints.

The next four offerings find the Poet musing upon the theme which, ultimately, drives the soul of every poet worth his salt – the generally indecipherable and oft maddening universal contradiction which is the fairer sex.

In A Plea for a Plot, Nordby rambles on a bit in anapestic dimeter concerning the ulterior motivations of women . . . and generously offering himself up as a sacrifice for their nefarious schemes. How altruistic of him . . .

In Girls Will Be Girls – I Hope!, he presents a fast-paced pair of stanzas in coupled anapestic feet, that sums up the timeless, universal male lament regarding females and offers a simple, sanity-saving solution – just accept it and enjoy. Yes, yes, the penultimate line breaks metric form, having four syllables rather than three . . . just accept it and enjoy.

In A Report From Hell, Klaus offers some insight in the source of summer’s sweltering heat, in iambic tetrameter – it’s the hotties that make it hot . . . Duh!

In Crazy Love, he employs iambic trimeter, as well as some semi-surreal imagery, to apply the “universal male lament” to his own, particular experience.

The final Poem Green, Miss ‘N Me, is indisputably the best. Employing a repetitive, all “A” ending rhyme-scheme, this poem is a carousing, upbeat jaunt, that navigates the reader through a series of three of four highly-alliterative and concretely-illustrative stanzas, in which Mr. Nordby outlines for us the specifications of his ideal mate; psychologically, physically and intellectually.

In terms of prosody, Miss ‘N Me is a poetic treat. Each four line stanza uses a punctuating meter variation to subtle, yet dramatic effect. The first three stanzas consist of three lines of iambic tetrameter, punctuated by a final line of iambic trimeter. This variance serves to manipulate the reader’s tempo, creating a lyrical effect which is the equivalent of “cornering on rails” in a high-performance sports car; he steady pace of the tetrameter abruptly accelerates through the “curve” of the final trimetric line, then resumes its flow in the next “straight-a-way”. The fourth and final stanza, ends with a nine-syllable coast across the “finish line”. The “race” is over . . . and Nordby wins.

In terms of overall prosodic and thematic artistry, Poems Green, contains only one poem, the last, which stands among the short list of the best poems in the Poems Green Purple Blue Red volume. They are, ultimately, but an appetizer to the feast which is to be found amongst the pages to come. But, they are a prelude to a feast.

Part 2: Poems Purple

Klaus Nordby says that his Poems Purple are “too didactic”. Well, they certainly each have a point to make, but, for the most part, the didacticism is well couched within finely crafted verse. Profundity is fine with me, as long as prosody does not suffer. And, in Poems Purple, prosody is evident.

In Points of View, Nordby offers a study of particularity (trees) and universality (forest) in two stanzas, consisting of a total of eight heroic couplets. It would seem that Klaus sees both the forest and the trees with concrete, principled clarity.

In Take It or Leave It, the poet considers existence versus nothingness in anapestic trimeter. This poem is fairly didactic and its conceptual content may be difficult for any reader who is not already familiar with the truly profound statement being made. However, the “ictus”, or rhythmic flow, of the poem makes it worthy of reading aloud for sheer perceptual delight. The only hitch comes in the third line of the first stanza, where Nordby inserts an extra anapestic foot. Ah well, he chose to leave it, and I’m willing to take it.

In The Vault and the Law, Klaus considers the crushing weight of an inverted moral code and lauds the value of self in six, six-line stanzas of coupled anapestic dimeter. The metaphors are well conceived. The prosody is well crafted, especially the rhyme-scheme. Within each stanza, the first, second, fifth and sixth lines share a common end-rhyme, while the third and fourth are of alternate coupling. Didactic? Yes, highly. But, there is so much to take in, with the wide variety of interesting poetic elements, that one hardly notices. This poem requires (and is worthy of) multiple readings, if one is to experience all that it has to offer.

In Because, Nordby offers a profound vision of man’s relationship to nature — explore, discover, learn, obey, command, create — with body and mind. The message is profound and its many implications are abundant. However, as well conceived as the message may be, it is roundly out-shone by the poem’s structure. It’s hard to decide exactly where to begin an analysis of the structure, there is so much, made to appear so simple. There are two stanzas, each of which is a poem in itself. Each stanza contains ten lines existing as five rhymed couplets. Each couplet consists of a line of iambic trimeter followed by a line of iambic tetrameter, which serve to force the reader to ascend a series of steps. One does not simply read this poem, one climbs it! There is so much to take in and savor with the interesting metric form and the way the beat and rhyme flows from the tongue when the poem is read, that one may not notice, upon first blush, how the visual, side-by-side, nature of the two stanzas in physical space on the page, ingeniously serves as a subtle visual symbol that aids in concretizing the poem’s theme! This poem is NOT just words written on paper, conveying concepts. This poem is a lyrical sculpture and a perceptual journey! It is a masterpiece.

In The Rights of Spring, the poet serves up a homegrown feast of coupled anapestic dimeter, in four, eight-line stanzas, which employs some subtly effective alliteration, scattered throughout. The main course is the excellent use of metaphor to concretize a very abstract theme — teleology. I’d say that Nordby’s actions have achieved the goal to which he directed them.

In Illuminatus, Klaus shines a poetic light upon making the best of metaphysical circumstance. If the reader is unaware that the poet is a master photographer, then the concretizations used herein my seem a bit arbitrary and confusing. Fortunately, for me, I do not have that problem, so I can fully enjoy this four quatrain treat of iambic tetrameter, which employs some excellent repetition of rhyme.

In The Tables Returned (view second page here), Nordby laments the philosophical shortcomings of a great poet of the past — William Wordsworth. This is the longest poem in the collection and my least favorite. Don’t get me wrong. I am a fan of Wordsworth’s poetry. I also completely agree with the message presented in the poem. However, this poem really is more didactic than poetic. Throughout, much of the language seems forced; caught between the “rock” of expressing a message and the “hard place” of metric duty. But, self-indulgence is mother’s milk to a poet and must, occasionally, be excused.

In The Art of Second Sight, Klaus offers four heroically-coupled stanzas, each consisting of eight lines. Contained within is an exploration of his vision of reality — reflected, imagined, re-created and shared with another who comprehends and appreciates. This poem provides a poignant look into the process and motivations of the soul of the artist. It is another masterpiece of Purple.

Poems Purple is a significant step up in overall prosodic and artistic quality from Poems Green. There are four noteworthy poems contained within. Illuminatus is very good and The Rights of Spring is excellent. But, there are two Purple offerings which I consider to be true masterpieces: Because and The Art of Second Sight.

Part 3: Poems Blue

Klaus describes his Poems Blue as “a tad sad”. His poetic stylings are often subtle and even understated, but, for some of the poems in this section, “a tad sad” is quite the understatement. “Tear-jerking”, “heart-wrenching” and “soul-rending” are more appropriate descriptors for some of these verses.

There is a common theme that is reprised throughout the majority of the blue poems – loss. The painful emotions conveyed by the poems in this section make it the most difficult to objectively evaluate. Also, the intensely personal response that one has to the content of these poems will naturally evoke some very specific memories in the reader, along with the corresponding personal emotional context. I can discuss the prosodic mechanics and the use of language, but, ultimately, it is Klaus’s ability to express his own emotional context, in a way that renders the personal universally accessible, that makes the best of these poems true masterpieces.

The first offering in this section, A Vision Impaired, finds the poet lamenting the unsavory details which oft underlie that which appears beautiful at a distance. The metaphor which is employed in this Shakespearean sonnet serves on myriad levels. The prosodic structure is intact and the visceral imagery is striking. It is a very good work, though its thematic metaphor may not be emotionally accessible to many readers.

Cries from the Past is a somewhat embittered inquiry, casting light upon the frustrations of the unacknowledged genius in a culture which enshrines mediocrity. There are a few rough spots in the iambic tetrameter, but there is some superb imagery and a tangible air of indignity toward injustice.

Thematically, By Way of Goodbye is poignant and personal. Maintaining one’s intellectual integrity in the face of opposition from those to whom one has emotional ties is heroic, but painful. The first seven lines of this eight line poem are written in a fairly fluid anapestic trimeter. However, the final line contains a tenth syllable and doesn’t properly conform to any established meter. I am unsure whether or not this was intended as a structural metaphor of non-conformance for thematic purposes or not, but it is a bit jarring.

The Song of Shells is an interesting prosodic composition. This poem, consisting of five, five-line stanzas, is notable for its rhyme scheme — AAABB BBCCC BBCCC BBCCC AAABB — written in iambic pentameter. The poem’s theme, concretized through a metaphor of singing shells, is well constructed. Through the first four stanzas, one reasonably wonders why this poem is not located in Poems Purple, but the final stanza is unmistakably Blue and its bittersweet flavor lingers beyond the final syllable.

A Real Gem consists of eight lines of iambic tetrameter that lives up to its title. As with most real gems, it contains (what I consider to be) one minor flaw – its contrivance of two syllables from the word “faked”. But, is it really a flaw? I don’t know. Considering that it is an affectation which is used in a line of verse about affectation, it is possible that this usage is a deliberate element. This poem employs such an exquisitely crafted metaphoric theme that this gem’s single flaw may not be a flaw at all. This is an elegant masterpiece.

What Felines Feel is six alternating quatrains of iambic tetrameter which makes good use of alliteration, sprinkled throughout. But, as is often the case with Nordby’s poems, the real star of the poem is the superb thematic metaphor and some excellent visual concretes. The playful use of language and rhythm, throughout, makes the final stanza’s morose longing and sense of loss all the more poignant. This is a great poem.

In I Should Have Known, Klaus presents two five-line stanzas concretizing a simple universal theme – mortality and loss. The rhythmic structure of this poem is extremely effective. The rhyme scheme is ABABB CDCDD. The refrained end-rhyme at the close of each stanza sets a tone of reflection. But, it is the meter variations which really drive the mood, through forced tempo. The A and C lines are seven syllables of three metric feet (iamb, iamb, amphibrach), while the B and D lines are six syllables of iambic trimeter. This repetition of variation creates a “swell and release” ululation, to great effect.

Declining Charon is a Shakespearean sonnet that exudes its author’s agony with a melancholy grace and a heart-wrenching spasm. There is a break from strict metric form in line seven, which contains only four iambic feet, rather than the standard five. The impact of this shortened line is truly profound and simply cannot be over-stated. It is a choked, violent sob in the midst of a gentle, constant weeping. This singular, uncontrolled emotional outburst is spine-chilling and, every time I read it, I feel the urge to weep on the poet’s behalf. This is one of the greatest poems ever written and it is my honor to have read it.

Choice Parts is another metaphoric delight. It is seven, four-line stanzas of anapestic trimeter with alternating end-rhyme. The poem’s theme, of two souls whose love is divorced by irreconcilable differences of metaphysical worldview, is elucidated through a well-constructed metaphor. But, it is the poet’s use of language to create a visual image of rich, perceptual clarity that elevates this poem to greatness. Nordby paints a scene in words that one does not so much read as watch unfolding before his eyes.

Allies and Aliens is a poem that seems (to me, anyway) a bit out of place in Poems Blue. It is a fine poem, consisting of three, three-line stanzas of anapestic trimeter. The third line of the second stanza is a bit unwieldy and presents a slight hiccough in the otherwise smooth ictus of the poem. The imagery and metaphor are excellent and the theme is truly profound. However, I just don’t see this poem as being “sad”, at all.

The Truth About the Blues is a modified sonnet that breaks strict rhyme scheme, with the final coupling revisiting the A end-rhyme. There is some very compelling imagery throughout and the conceptual payoff presented in the final couplet is worth the read. However, throughout the poem, I felt an emotional disconnect that seems to come as a result of the author’s determined efforts to conform his content to meter, leaving me with a sense of the “mechanical”.

A Life on Earth is a profound and subtly sensual poem. In four sinuous stanzas of alternating iambic trimeter, the Poet ruminates upon a life of purpose and his own mortality. Structurally simple, yet exquisite in its elegance, this is another deeply satisfying masterpiece and is the perfect finale to Poems Blue.

Poems Blue, though several of its offerings plunge the reader into the emotional depths of despair, is a significant, upward leap, artistically. The Song of Shells, A Real Gem, What Felines Feel, and Allies and Aliens are all poems of outstanding quality and worthy of great praise. However, Choice Parts, A Life on Earth, and Declining Charon are masterpieces of the highest historical order, each for a different reason, and, as a group, illustrate the remarkable ability of this poet to exercise a mastery of all the prime attributes of poetry.

Part 4: Poems Red

Before I consider the poems in this final section, I’d like to take a moment to consider the book as a whole. The poems found within this book are each individual works of art, worthy of contemplation and enjoyment as such. But, Klaus Nordby is not merely a poet; he is, as the saying goes, a “man of many parts”. He is a visual artist and a master photographer and graphic designer. He has worked harder than most mere mortals can possibly fathom to create a book which is a complete, integrated entity. Its every aspect, from the typographical considerations, to the physical layout of print upon the page, to the materials from which it is made, to the graphical designs of the cover, compositions of color inclusion, and many other things, which I am not competent to evaluate or possibly even recognize, has been meticulously crafted. The result is a perceptual object, both in its PDF and physical book incarnations, which is far more than a simple, utilitarian vessel for the containment of poems. The book itself is a visually poetic composition. You would serve yourself well to take some time to study it as such.

Klaus claims that his Poems Red “aren’t nearly amorous enough”. With all due respect, I beg to differ. This passionate collection lays the poet’s heart and soul bare for all the world to see. It is bursting with love and courage and prosodic prowess.

There are 16 Poems Red, the most numerous of all the sections in this collection. Unlike the other sections, I have chosen not to consider every individual poem in this grouping. Rather, I will focus on the handful that I consider the best.

In The Spirit of the Sun, Nordby restructures the sonnet to suit his purpose. Rather than the traditional iambic pentameter, he writes in iambic trimeter. This alteration significantly increases the pace from the more languid flow of the Shakespearean form, thus creating a greater emotional intensity, which matches that of the poem’s theme. It is an excellent illustration of form following function. The great triumph of this poem is the combination of emotion and clarity with which it expresses the potential reward and risk inherent in opening one’s heart and soul to the fiery touch of a burning, passionate love.

The Concert of Consorts is another altered sonnet, written in iambic trimeter. It is a prosodic explosion, culminating in a sustained, impassioned burst that is the visceral emulation of the climactic crescendo of love’s ultimate concrete expression. This poem is a singular moment of rapture, captured and sustained. It is a frozen flame. It is a convulsion of passion, paralyzed and preserved. It is perfection.

In The Frost Giant, Nordby considers a theme which has haunted lover’s hearts since the dawn of Man – the aftermath of having loved and lost. Another sonnet, written in the altered trimetric form that Klaus has made his own, this poem employs a simple thematic metaphor to express a profound truth – the experience of a great love, for however brief a time, leaves one transformed . . . and better for the experience.

Why Red, O Rose? is a masterpiece. Within its four, six-line stanzas of alternating iambic tetrameter, there is a story of discovered passion, a heart broken, a mind searching for answers and an acceptance of a soul and perspective, forever altered by an enduring memory. The metaphor and imagery are superlative, but in this case, it is the subtleties of the poem’s sonorous ictus, which drives its haunting rhythm and lingers upon the tongue and soul. The placement of internal rhyme, alliterations and assonances create a rhythmic undertow and a forced variation in tempo, despite the consistent underlying meter, that leaves an appreciative reader breathless and, curiously, uplifted, despite the moroseness of the conceptual content.

Eternal Wealth, is, quite simply, my favorite poem in the history of poetry. It is a Shakespearean sonnet, unaltered in form. There is no breathtaking originality of structure on display here. There is no fascinating sensual elegance created by unusual alliterative or assonant qualities that captivate. In form, it is a simple, competent sonnet. What makes it so incredibly powerful, is what it has to say. I am not talking about didacticism. It doesn’t seek to teach. That which it expresses cannot be taught. It is not an expression of explicit philosophy. It is the soul of an artist, laid bare, for all the world to see, in a moment of profound and powerful honesty. It is a vision of a visionary, overcome with appreciation for those who appreciate. It is an epiphany, held aloft and blazing brightly. It is art which contemplates itself, its purpose and its own unfettered triumph. It is the expression of that which cannot be contained in words, contained in words. It is God.

It has been a great honor to have been helpful, in some small way, in the preparation and production of Klaus Nordby’s Poems Green Purple Blue Red. I have been an avid lover of poetry for more than 30 of my 39 years. I have been a serious student and writer of poetry for over two decades. I know good poetry when I read it. Shelley, Poe, Keats, Frost, Kipling, Coleridge, Herrick, Donne, Byron, Wordsworth, Tennyson, the Brownings and other masters have given me a lifetime of solace, cheer, provocation and inspiration. While Nordby’s poetic corpus may not rival that of those historic masters in quantity, poems such as Miss 'N Me, Because, The Art of Second Sight, Declining Charon, Choice Parts, A Life on Earth, The Concert of Consorts, Why Red, O Rose?, and Eternal Wealth, among others, are of a quality that, in my estimation, has earned him a well-deserved place among such immortal names. There are poems in this collection that should be studied in literature classes as true, historic masterpieces.

Finally, I'd like to say that reading these poems and getting to know their author has made my life better. Thank you, Klaus. Well done. |